I was asked to talk at the Centennial Celebration of McLean, Virginia, about being the daughter of "McLean's newspaperman." That would be my father, Bill Elvin, owner, editor and publisher of a weekly, the McLean Providence Journal, for 30 years. Here's what I said about that:

Dad was an old-fashioned, "shoe-leather reporter." He loved writing and publishing news about McLean up until the very last.

The hallmarks of his work were integrity, fairness, and honest reporting without embellishment or editorializing.

He knew from early on that he wanted to be a reporter. While attending the University of Michigan, he was assistant editor of the Michigan Daily. During World War II, he served in General Patton's Third Army — they met the Russian Army at the end of the war in Austria. Dad was selected Designated Vodka Drinker by his company for the occasion, and was interviewed by a reporter for Izvestia. (I never got whether the interview took place before or after the vodka.)

After the war, he worked for the Washington Star for ten years, then decided to venture out on his own and bought the Providence Journal from Richard M. Smith. Some people called the paper under Smith a gossip sheet that served as a vehicle for Smith's extreme segregationist views, which couldn't have differed more from my father's. Dad charted his own way, steering away from editorial opinion, given "the facts, just the facts," and trusting the readers to form their own conclusions.

He intended to paper to be a local McLean paper from the very beginning. When he took over, paid circulation was about 2,000. He sharply reduced coverage of communities outside of McLean, losing about half the subscribers. But the additional news of McLean eventually won over new readers, and the circulation went to 2,000 and beyond.

The Providence Journal covered local fairs, back-to-school, holidays, elections, and material for columns such as In the Services and In the Colleges. He appreciated the unintended compliment from a reader that went, "I do not like your paper and am re-subscribing only for purposes of information."

Once when I attended a joint McLean-Marshall High School reunion, I noticed that in one of the suites alumni used to bring out old photos and memorabilia, clippings from the Providence Journal were laid out on table in abundance, yellowed by time. A glorious moment for one boy at a football game, a notice of enlistment of another, accomplishments, moments of their lives all noted in their local paper. When I told Dad, he was so pleased. He said emphatically, "That's what I always wanted it to be. The hometown newspaper."

Dad had acute powers of observation. I remember one afternoon as he mowed our lawn, he noticed a car parked on our street. It was unusual for anyone to park there, since the street was narrow and all the houses had long driveways. When he saw the car, he jotted down the license plate number — he was never without pen and paper, even doing yard work. Detectives appeared a short time later, fanning out to investigate an incident in the neighborhood. When they saw my father in the front yard, they approached him and asked if he'd seen anything out of the ordinary that day.

He told them about the car and in his understated manner, pulled out his notepad, read off the plate number, gave the model, year and color of the car, and the exact time of day he'd seen it. With that information, the detectives were able to send out an APB. Soon enough, a suspect was apprehended on the Beltway and was subsequently convicted of raping a teenaged girl who lived up the street.

In February of 1958 a double snowstorm prevented him from delivering the papers from the printshop to the post office for mailing. The snow was deep and blinding, and high winds created whiteout conditions. At the last moment, two young women on horseback rode up the rode toward the printshop and offered to take the papers on horseback. Saved by the Pony Express! [You can read the further details of this in my March 6 blog, below.]

I can remember driving from McLean to Oakton to the old print shop where the Providence Journal was churned out once a week in the olden days. It was one shack tacked onto the other. The floors were dirt, the presses were noisy, it was dark, and it smelled of printers' ink. All the men who worked there seemed covered in ink. And Dad loved that part of the weekly newspaper routine just as he loved all aspects of being editor, publisher, chief reporter, owner, and chief cook and bottle washer of the Providence Journal.

Things of course modernized and changed, but what never changed was his love of reporting or his integrity. By his example he taught me a great lesson: doing something for a living that you love and that is meaningful matters much more than money or satisfying someone else's wishes.

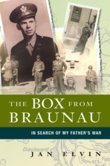

The picture shows my father a little over 50 years ago, trying to get some work done. My brother George is helping.